[This was somewhat up to date in 2011 when it was first written but it is decidedly out of date at this point. The train has not only left the station for tPA but has indeed morphed into some kind of time travelling, flying train from Back to the Future at this point. I remain sceptical (like many in EM) about the evidence base for tPA in stroke but I keep this here as a useful reminder of how important it is to read the literature in detail]

This has been an interest of mine for a while. So much so that I’ve gone and written a slightly meandering epic on it all…

All the hospitals I have worked in recently have well set-up and well ran acute stroke services which involve lysis. Despite my scepticism on the evidence base for lytics in stroke, medicine and emergency medicine in particular is a team sport so just because I find myself in the position of scepticism does not allow me to deny patients access to other professionals and treatments that I may differ from. Just remember you work for a hospital – don’t get fired over it. If your hospital does tPA for stroke and you’re involved then you’d be best to do it as well as you possibly can.

I’ve endeavoured to keep this somewhat up to date but the sheer volume of published literature makes it difficult.

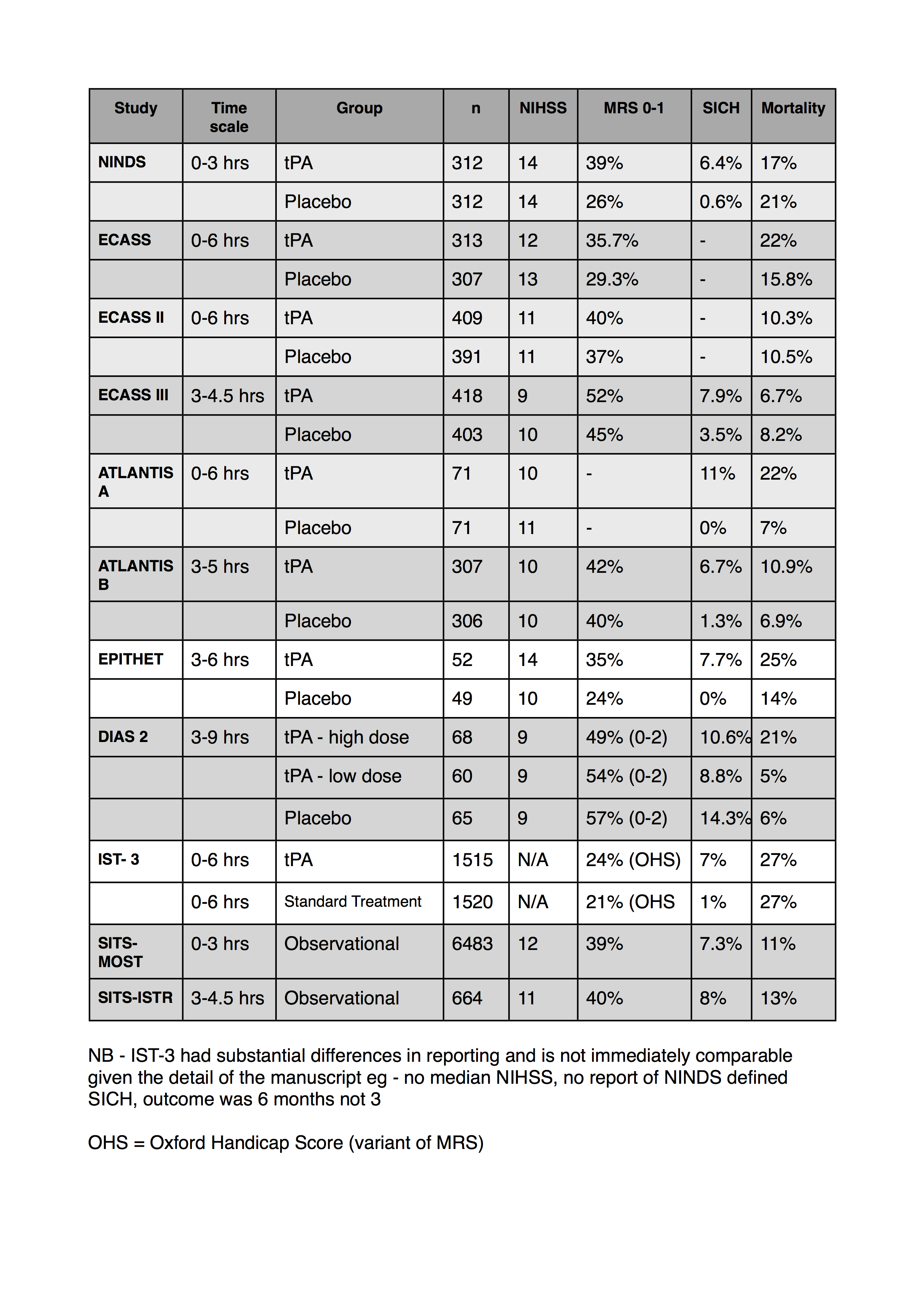

I’ve also collated a table of some of the numbers from the studies regarding outcomes and adverse events. I’ve tried to use the NINDS definition for SICH if I can find it in the corresponding paper. Let me know if I’ve got any of the numbers wrong.

I’ve added my thoughts on IST-3 at the very bottom and updated the table below.

- I can’t find MRS data for the atlantis A trial

- only the most recent ECASS data reported a NINDS definition of SICH

- the SITS studies are both observational registry data

- This was compiled from data in 2011. Obviously there’s lots more stroke data than this

I’ve presented on this a couple of times but this is gonna require a few parts, so be patient with me. This is not quite a deep-dive, more of a shallow dive you might do with a snorkel rather than a full on SCUBA.

Thrombolysis for stroke is a controversial treatment. SAEM previously had a statement saying

It is the position of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine that objective evidence regarding the efficacy, safety, and applicability of tPA for acute ischemic stroke is insufficient to warrant its classification as standard of care. Until additional evidence clarifies such controversies, physicians are advised to use their discretion when considering its use

This has recently been retracted

UPDATE 2012: The Australian College of Emergency Medicine have a nice little statement on tPA in stroke that can be found here.

Many don’t see it as controversial at all, just an underused treatment that has solid and conclusive proof behind it. The drive to treatment has inspired a big public health initiative

I don’t mean in this series of posts to discard the idea that thrombolysis is useful in ischaemic stroke, I just mean to explore the evidence for its use and show that its evidence base makes it a controversial treatment, I would argue it makes it an experimental treatment.

Thrombolysis came into every day use with its role in STEMI; initially with streptokinase and then succeeded by tPA.

The evidence for this involves thousands and thousands of patients in high quality RCTs (GISSI-1 12000; ISIS 2 17000; GUSTO I – 40000)

In addition, in STEMI we have a clearly defined disease process, with a quick and easy to interpret diagnostic test with some important, but usually easily defined mimics.

In contrast, the origin of the use and license for tPA in stroke is based on a single RCT in the mid-90s which was based on 300 people. (I know there were 600 in the trial but I’ll expand on that later).

The more recent discussion (and indeed the AHA level I recommendation) for 3-4.5 hrs is based on the ECASS III trial and I’ll cover that too.

Let me say again, my aim is not to prove to you that tPA for stroke is of no use in stroke, my aim is to make it clear that we are not yet at the stage of being able to say definitive things about its role.

There have so far been 11 published RCTs (that I know of) of the use of thrombolytic therapy for acute ischaemic stroke.

2 of these can be regarded as positive, 9 as negative (the EPITHET trial is a bit unusual in its outcomes and I consider it negative but we’ll cover that). Please take note of that.

Three of the earlier ones concerned the use of streptokinase (ASK, MAST-ITALY, MAST-EUROPE). Two were negative, one was stopped early due to harm. I’m not gonna cover them in this series as no one is actually using strep for stroke these days. I’ll put a link to them in the references.

Let me start with the key trial in this whole thing – NINDS

PATIENTS

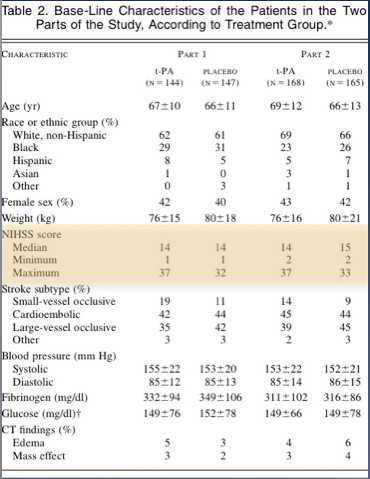

First thing to note is that this was actually two trials reported as one.

Part 1 assessed changes in neurologic deficits 24 hours after the onset of stroke as a measure of the activity of t-PA

Part 2, the pivotal study, used four outcome measures representing different aspects of recovery from stroke to assess whether treatment with t-PA resulted in sustained clinical benefit at three months.

Part one wanted to assess whether if you were given tPA or placebo whether you would have a 4 point improvement in your NIHSS at 24 hrs. This is very different from living independently at 3 months; something we really care about.

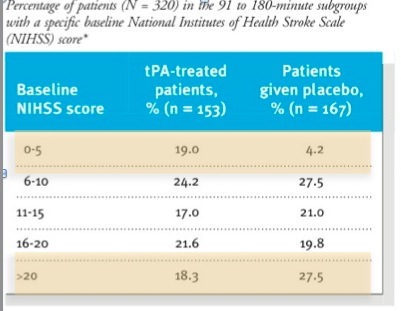

In both parts the time to treatment was divided into two: 0-90 mins and 91-180 mins. There was a requirement for equal numbers in both the early and late groups. It is extrmely difficult to have a stroke, get to hospital, get seen, get a CT and a decision to get tPA within 90 mins. Most of the people given thrombolysis in real life are in the 91-180 min group. In some of the other trials with a more liberal protocol (up to 6 hrs) the average time is around 4 hrs.

In NINDS the radiographic criteria were a base-line computed tomographic (CT) scan of the brain that showed no evidence of intracranial hemorrhage. Those of you who have read about stroke lysis before wil realise that this is not considered an appropriate CT criteria these days. Indeed I’ve heard a few neuroradiologists and neurologists say that you shouldn’t be giving tPA unless you can see some early signs of infarction on the base-line scan.

OUTCOMES

You should have a primary outcome for your trial. In NINDS they had 4. That’s kind of a cheat. The more you have, the more likely you’re gonna have one turn positive.

They also included the NIHSS as one of their 3 month outcomes which which raises an important point. The NIHSS is a good marker of stroke severity but it’s not necessarily linear. The difference between a 12 and 16 is not necessarily the same as the difference between a 20 and a 24. So if you see a 4 point difference in the NIHSS at 2 hrs or 3 months, that doesn’t mean you have a comparable clinically significant improvement. This is not what the NIHSS had been used for before – the authors even state this in the paper.

They sensibly defined new stroke and bleeding as adverse events but note their definition of symptomatic haemorrhage

A hemorrhage was considered symptomatic if it was not seen on a previous CT scan and there had subsequently been either a suspicion of hemorrhage or any decline in neurologic status

Again, if you’ve been following the literature, you’ll see that this definition varies from study to study. One of the problems that makes comparing these results difficult.

If you died in this trial, all that got recorded was your death and the presumed cause, if you died suddenly from an ICH and you didn’t get a post-mortem (this wasn’t a requirement) then this wasn’t noted.

RESULTS

The first thing is to look at the patients we’re interested in. For brevity I’m only gonna look at part 2; the group that had 3 month outcomes assessed (the only thing we really care about).

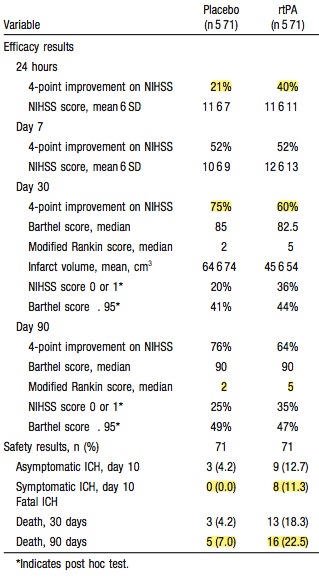

(For the record part 1 was negative in its primary outcome.)

If you look at the table in the paper they look reasonably well matched. Mann in the Western Journal of Emergency Medicine put some work in on this and eventually got the full data set from the NINDS investigators and they found some more significant differences in the two groups than is apparent in the table in the NEJM

The tables show that patients in the placebo group had more severe strokes.

This doesn’t mean anyone fiddled the trial so that the sicker patients ended up in the placebo group; this variation is easily possible when you have two groups of only 150 each.

Having said that, the tPA group fared better in all 4 outcomes. there was a 12% absolute difference in the Modified Rankin Score (this has become the standard for outcomes in stroke research – a score of 1 or less is considered good outcome)

On the basis of Part 2 of this trial (one group of 150 who got placebo, one group of 150 who got tPA) tPA got FDA approval.

Despite calls for further research, once it got FDA approval, people came out and said it would be unethical to repeat a placebo controlled trial at 0-3 hrs as tPA was “proven” to be helpful.

So much for the NINDS trial.

Next I’ll try and cover some of the other trials arranged by the groups who investigated them.

SITS-ISTR and SITS-MOST

You may have seen these two trials. The most important thing to be said about these is that they are not trials.

They are reports of voluntary registry data (caveat – the european license dictated the setting up of these registries but that doesn’t mean it’s enforced) of patients who recieved thrombolysis. This is purely observational data of patients who someone thought should get tPA.

Despite this the authors do multiple comparisons with historical controls – chosen favorably from amongst the prior trials.

This is comparing apples and oranges. I hope it’s clear that the patients getting tPA in the SITS papers are different patients than those in the other papers. Therefore it is not fair to claim comparable efficacy.

This is a major objection to the thrombolytic literature in general, and in particular it’s combination in meta-analyses. The NNT summary covers this idea well.

The ATLANTIS trials

The ATLANTIS trial was presented in two parts. Initially it was intended to be one trial, looking at tPA form 0-6 hours.

Two things happened:

- Once the NINDS study was published, the investigators scapped the idea of giving placebo to the o-3 hr patients as this was considered unethical.

- the safety monitoring committee found concerning results in the 5-6 hr patients given tPA.

Thus Atlantis A was a trial of 0-6 hrs that was stopped and Atlantis B was a re-launch taking patients at 3-5hours.

ATLANTIS A

PATIENTS

had similar inclusion/exclusion criteria to NINDS, but allowed for the investigators to exclude patients with “Any other condition that the investigator feels would pose a significant hazard to the patient if rtPA therapy were initiated”

OUTCOMES

They had two primary outcomes (again this is a little bit naughty)

- a reduction in NIHSS at 24hrs and 30 days

- a reduction in infarct size

I would contend that both of these outcomes scream SURROGATE MARKER.

RESULTS

most were thrombolysed after 4 hrs. This is understandable – it was the early 90s after all; there weren’t many stroke teams about.

The strokes were less severe (a trend in every trial since NINDS) with a median NIHSS of 10 or 11 (it was 14 in NINDS)

Of the patients with an NIHSS>20 who got tPA every one of them (16 of them) was dead by 90 days.

I hope you’re convinced that this was a thoroughly negative trial by now

ATLANTIS B

PATIENTS

They took patients from 3-5 hours and changed the inclusion criteria subtly. Patients with a CT showing greater than 1/3 of the MCA territory involved were excluded. The basic effect is to exclude the bigger strokes. This is now ubiquitous in the newer trials.

OUTCOMES

they had the ambitious primary outcome of an NIHSS of 0-1 (on a 42 point scale!) at 90 days. In the secondary outcomes they had the modified rankin scale that we’re probably more interested in.

RESULTS

they recruited 600 patients, most of whom who got lysis at about 4 hrs or so.

Again they were less severe strokes – NIHSS of 10 in this trial.

Their primary outcome makes fascinatiing reading

- 32% of placebo patients and 34% of tPA patients had an NIHSS of 1 or less at 90 days.

That deserves comment, even though it’s a recurrent finding in all the trials. People with strokes sometimes do great no matter what we do. Or perhaps more accurately. People with strokes will often (if you count a 1/3 of the time as often) do really well with good nursing care and good stroke management. Let me quote the cochrane review of stroke units (comprising, dedicated nursing, medical, OT and physio and feedings care.)

Stroke patients who receive organised inpatient care in a stroke unit are more likely to be alive, independent, and living at home one year after the stroke

Over all in the studies the placebo group often does well (MRS <2 in 35-45% of placebo patients). We all know people with severe strokes who are “prisoners in their own bodies” but this is probably not as high a percentage as you thought it was. They are also not likely to be eligible for tPA anyhow (NIHSS greater than 25 or a nasty CT)

As for secondary outcomes, like that pesky one – death, placebo won with mortality of 7% for placebo and 11% for tPA

These trials are important when it comes to reading ECASS III as it claimes postive effects on patients treated beyond the 3 hr mark, whereas these trials showed that people did really poorly beyond the 3 hr mark.

The ECASS trials

ECASS

Pretty similar in aims as the ATLANTIS study we talked about last time.

PATIENTS

- 0-6 hrs

- they excluded severe strokes and people with more than minor early signs of infarction on CT (something NINDS didn’t differentiate on)

- they also used a slightly bigger dose of tPA (1.1 vs 0.9mg/kg)

OUTCOMES

- barhel index and modified rankin score

RESULTS

- 300 in each group

- median NIHSS slightly higher than more recent trials at 12/13

- they excluded over 100 on the basis of CT signs- remember this the next time your general radiologist has given you a report simply saying no bleed. note that these 100 they excluded were excluded after inclusion in the trial after review of CT scan by a study radiologist. That’s a bit naughty as you might suspect.

- mortality was 22% tPA v 15% placebo.

- it’s difficult to tell about symptomatic intra-cerebral haemorrhage as they didn’t define this clearly. Overall ICH was 43% tPA vs 37% in the placebo group

- tPA did make a 6% absolute improvement in MRS <2 (35%v29%)

If the treatment increases mortality then you can see why I consider this a -ve trial.

ECASS II

Not to be deterred they tried again

PATIENTS

- this time they had more stringent CT criteria and tight BP control and hoped this would be better

- still 0-6hrs

- randomised in blocks so as to have some in the 0-3 hr group and some in the 3-6 hour group.

OUTCOMES

- an MRS less than 2

RESULTS

- 400 in each group,

- most at about 4 hrs or so

- again they excluded 10% in each group retrospectively based on CT findings. So despite a strict definition and extensive training of all the radiologists for the study, they still called it wrong 10% of the time.

- 40% (tPA) had MRS<2 vs 37% in the TPA group. This was not of any statistical significance. This difference was the same whether you were in the 0-3 hr or 3-6 hr group

- mortality was equal at 10%

- in terms of symptomatic intracerebral haemorrhage it’s stil difficult to tell as despite giving a nice clear definition (any new blood on CT associated with clinical deteroration) they don’t give the numbers in the manuscript that I can find. They say it was 2.5 times higher, they just don’t give the numbers

This trial is negative by their primary outcome but mortality at least remained equal. In addition they more than doubled the rate of SICH.

ECASS III

the one that got all the attention a few years back and got the guideline reccomendations extended out to 4.5 hrs

PATIENTS

- the usual stroke patients with a CT and again there were CT exclusion criteria if your stroke was too big

- 3-4.5hrs only

- they also excluded NIHSS >25 which is new for this study

OUTCOME

- the now ubiquitous MRS of <2

RESULTS

- 400 each group

- took 4 years to recruit 800 patients from 130 centres (that’s 1.5 patient per year per centre)

- 52% in tPA group and 45% in the placebo group had an MRS<2

- mortality was 7.7% in the tPA group and 8.4% in the placebo group

- Symptomatic intracerebral hameorrahge was bizzarely low at 2.4% (still 10 times mor than placebo) despite the fact that overall intracerebral bleeding was 27% in the tPA group and 17% in the placebo group. This is probably explained by the following statement:

In our study, we modified the ECASS definition of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage by specifying that the hemorrhage had to have been identified as the predominant cause of the neurologic deterioration.

Remember that the investigators get to decide this, and this allows them to define SICH pretty much as they want.

- Median NIHSS of 9 in tPA group and 10 in the placebo group. (p-value of 0.03 for this). People had more severe strokes in the placebo group.

- 7% had previous stroke in tPA group and 14% in the placebo group (p-value of 0.03 for this). More patients in the placebo group would have had an MRS >0 before they even had their second stroke

- they try to adjust for the significant baseline variations in the groups with logistical regression – they tell us that there was still a significant difference after adjustment but you have to be a believer in logistical regression; that it can accurately adjust for not just the stated confounding variables but all the ones that you don’t know about.

By their trial design and definitions this is a positive trial, you just have to decide if the problems outlined above are enough to call it into question.

Note that this trial enabled recommendations that tPA is safe for 3-4.5 hrs. This despite that all prior trials treating patients at the same time periods were killing patients and were terminated early.

DIAS-2 & EPITHET

I’m reviewing these two trials as they both looked at what could be a really interesting and useful idea – using imaging to select patients who would most likely benefit from tPA.

This isn’t particularly important to understand fully but in an ischaemic stroke there is such a thing as an ischaemic penumbra – an area of brain tissue surrounding the central infarct; that if perfusion is quickly reestablished may recover well.

The idea is to use imaging (mainly CT perfusion or diffusion weighted MR) to identify such patients and target treatment at them and not the others.

There is lots or pre-RCT research on this if you’re interested, trying to define what all the above actually looks like in practice, but below are the RCTs involved.

EPITHET

There’s really two things going on here. An RCT for tPA v placebo and an observational imaging study to define the useful penumbra.

PATIENTS

- 3-6 hrs with stroke and a negative baseline CT (or sometimes MRI)

- exclusion criteria fairly extensive and building on the work of the older studies. Kind of like goldilocks and the three bears, not too severe a stroke, not too mild, but just right…

- randomised to tPA v placebo

- before they got the study drug everyone got an MRI looking for the ischaemic penumbra – these results were looked at AFTER treatment and had no impact on deciding who got placebo and who got tPA

OUTCOMES

- primary outcome was a surrogate – infarct growth attenuation (basically did patients who got tPA have a smaller infarct on imaging.) This was to be based on a 90 day scan but there some problems with that as we’ll come to

- secondary outcomes included lots of imaging based composite outcomes including some clinical features.

- this means that the trial will be drastically underpowered to detect anything we care about.

- note the definition of symptomatic ICH is again changed:

ICH with significant clinical deterioration of ≥4 NIHSS points within 36 h of treatment, and parenchymal haemorrhage of grade 2 on CT (blood clots in >30% of the infarcted area with substantial space-occupying effect) adjudicated by a blinded committee

this is worth comment

- the change in definition is stricter and probably more accurate but let’s be clear – it favours tPA

- in all the trials adjudication of SICH is done by a central blinded committee. in some of the trials these are directly paid employees of the company making the drug. in a tPA trial if you’re asked to adjudicate on a case where the patient had deterioration and bleed following the study drug you know full well that they got tPA and not placebo. This means that you aren’t really blinded and there’s potential for bias in classifying patients as SICH. This is a problem for pretty much all the trials.

RESULTS

- 100 patients total (50 tPA, 50 placebo) – and yes you’re right that’s a tiny trial. Whenever’s there’s less than 100 in a group talking about stats in percentages bcomes kind of meaningless.

- in terms of their primary outcome it was a negative trial – they didn’t show a decreased infarct growth by geometric mean. But they reanalyse it with a different technique and guess what it looks much better (and they put it in the abstract too)

- the other thing to mention is that they couldn’t do the 90 day scan (which was part of the primary outcome) in a few patients, so they ended up with 37 in the tPA group (which started with 52) and 43 in the placebo group (which started with 49). The reason for this:

Day 90 imaging was not done for 19 patients in the alteplase group (13 had died and six were lost to follow-up) and eight patients in the placebo group (seven had died and one was lost to follow-up)

note the implications of that – they couldn’t do the 90 day scan because twice as many had died in the tPA group. Nevermind the “6 lost to follow-up” who may well be dead, especially as there was only one lost to follow-up in the placebo group.

They tell us that the mortality difference was non-statiscally significant and in a trial this small it’s always going to be hard to tell, especially when over 10% of the patients in the tPA group are “lost to follow up”.

It really matters what happens to those patients in such a small trial. If those 6 patients are dead then there would be a “statistical difference” in mortality. Whether or not there’s a statistically significant difference (and I doubt it matters here) then you need to decide whether that worries you or not.

- for once there was a baseline difference in NIHSS favouring placebo (14 v 10) which is to be expected when numbers are this small

- in terms of the thing we care about there was an 11% absolute difference in MRS <2 favouring tPA but remember in such a tiny trial this is 18 v 12 patients we’re talking about

- the rest of the paper is about the penumbra stuff and looking at who reperfused and who didn’t. And people who got tPA reperfused more often. Let me say again – this is a surrogate that I don’t really care so much about.

they make this statement in their discussion:

The EPITHET results support the use of reperfusion as a surrogate for outcome in future proof- of-concept stroke trials

having read the details of the trial and looked at the tiny numbers involved I’m not sure I agree.

they also make this statement in the results section of the abstract, the bit that most people will read!

Reperfusion was more common with alteplase than with placebo and was associated with less infarct growth (p=0·001), better neurological outcome (p<0·0001), and better functional outcome (p=0·010) than was no reperfusion.

- When I read that the implication is that tPA was associated with better functional outcome. There’s even a p value beside it. But if you’ve read the results as I’ve presented them or even better, you’ve read the trial then you know that’s not what was found

- What we see here is spin (and this is really important); there is nothing factually incorrect in that statement. It’s just that what they’re describing is 4 separate findings placed in a sentence to link the first few words (“reperfusion is more common with tPA)” with the last few words (“better functional outcome”)

- if you asked the trial to answer this question: is tPA associated with better functional outcome then the answer is NO.

DIAS-2

This is unique in a few respects:

- it used desmotaplase, a variant on alteplase. again there’s lots of basic background research on this and it may turn out that there’s something better or worse about it but in mechanism of action and class it’s similar

- it uses imaging to select the penumbra patients (either CT or MR); this is different form EPITHET in that the penumbra imaging part was only observational there. In DIAS-2 the imaging is used to pick out patients who will hopefully do better

PATIENTS

- 3-9 hr patients

- a similar “goldilocks” selection of patients to EPITHET; with the important addition of MRI signs – MR is much more likely to pick up signs of severe infarct and so allows you to be even more selective, even before you do the perfusion imaging

- a salvageable penumbra needed to be shown on imaging (MR or CT)

- 3 groups, high or low dose desmotaplase and placebo

OUTCOMES

- 90 day clinical outcome; which in this trial is a composite of mRS <3 (it’s usually mRS <2), NIHSS improvement and Barthel index

RESULTS

- 30% had no penumbra by imaging and were excluded. This varies from study to study but it’s a useful figure to keep in your head.

- n 180 patients (60 in each group)

- median NIHSS was 9 (remember in NINDS it was 14)

- in terms of their primary composite no difference was found in outcome but let me break it down a bit:

- mRS<3: placebo – 59%; low dose 54%; high dose 49% – PLACEBO SAVES THE DAY!

- SICH (by the new tPA favouring definition) was 4% in the tPA patients vs 0% in the placebo groups

- Of note if the NINDS definition of SICH is used then placebo jumps to having 15% rate of SICH and bizarrely tPA changes to only 9%. I imagine this is more to do with the imaging used (largely MR) and the size of the trial than it is with tPA being protective against bleeding. (he says tongue-in-cheek…)

- In terms of mortality there were 4 deaths in the placebo group, 3 deaths in the low-dose group and 14 deaths in the high-dose group. They give a table giving causes of death and suggest that the tripling in death rate in the high-dose group has nothing to do with the tPA. Hmmm

Their interpretation in the abstract is illuminating:

The high response rate in the placebo group could be explained by the mild strokes recorded, which possibly reduced the potential to detect any effect of desmoteplase.

This begs the question – if these low grade strokes (selected out by the finest imaging and clinical lessons learned from prior trials) do so well that we can’t see the benefit of this wonder drug then why the hell should we be using it?

Only a quickie this time.

I mentioned in the first part that I wasn’t planning to discuss the details of the MAST trials as they used streptokinase as the agent and this is no longer used.

In short both trials were stopped early due to increases in mortality

I re-read them and found this crackingquote from the authors of the second MAST trial. Note that at this stage MAST-I, MAST-E, ECASS I, and ASK trials had all been published and had increased mortality. Only NINDS had been published as +ve. This was 1996.

The possibility cannot be ruled out that the results of the NINDS trial are due to chance; the results of a single trial do not provide sufficient evidence of the efficacy and safety of a drug, especially when similar trials have conflicting results.

I can’t give you a run-down of the aussie ASK trial cause I can’t get access to mid-90s copies of JAMA through my library proxy. Maybe everyone was distracted by Dolly the sheep, or the dawn of the interweb. I wasn’t so much thinking about RCTs in the mid-90s as I was by getting my driving test. That now seems a long time ago… [cue weeping into beer…]

So what does this all mean?

My suspicion that tPA isn’t all it’s cracked up to be is fleshed out in the previous 4 and a half parts.

If I bored the teeth off you let me try a snappy conclusion

The evidence for tPA for stroke is problematic because

1) significant heterogeneity in the trials in terms of:

- CT definitions and exclusions

- variations in severity of stroke

2) significant base line variations (favouring tPA) in the populations of the two +ve trials

3) a predominance of negative findings overall (2 postive trials and 9 negative trials)

4) every single trial is either funded directly by the manufacturers or the authors have significant conflicts of interest with writers and researchers working directly for the company. NINDS may be an exception to this as the drug was supplied by genentech but overall finding was via the NIH. The article doesn’t provide detailed conflict information

Where I work mostly, the stroke team deal with any potential lytic cases. For once I’m very glad that EM in Ireland is dysfunctional enough that we’re not taking the lead on this.

For example – i’m not entirely sure how to approach informed consent on this. How do you explain the complexities of this to a patient?

Having said that…

My suspicion is that thrombolysis is beneficical for certain people with certain strokes, I’m not convinced we know who those patients are yet.

I find the overwhelming support for such a controversial and potentially dangerous (approved on the basis of a 300 patient trial despite multiple negative trials) treatment to be premature.

I think the way forward from here is to replicate the findings of the NINDS trial with a substantial population (as was done repeatedly with lytics for STEMI) in a non-pharma sponsored trial.

I used to say that there wasn’t the slightest appetite for this to be done.

But it’s nice to be wrong.

IST-3

Hopefully you’re aware of the IST-3 trial which hopes to finally clarify things. (IST-1 was one of the trials that showed aspirin was a good thing in stroke.)

It’ll have finished enrolling by the time this blog post is published.

Here’s a quick run-down of the trial

- 0-6 hrs with stroke

- no blood on imaging (i don’t see any mention of the subtle stroke signs in their protocol)

- randomised to tPA or placebo

- primary outcome is mRS 0-2 (remember in most trials it’s been 0-1) assessed by postal questionnaire or telephone interview at 6 months. It’s a bit disappointing that it’s follow-up by phone/post as that could cause problems if there’s a high lost to follow-up rate

- non-pharma funded and minimal conflicts in the authors (it’s very hard to have none!)

This is gonna be a 3000 patient trial. To put that in context, the cochrane systematic review of lytics in stroke has 2955 patients in it.

If any trial is gonna give us the answer then this one will.

So I look forward to having my mind changed! No doubt you’ll hear more from me when it gets published.

OK so IST-3 is out. It’s a big and important trial so make sure and read it. Stroke lytics get a lot of attention from EM folks, if only because we seem the only ones not convinced of its efficacy. Jerry Hoffman is probably the most important contentious voice but he’s by no means alone. Ryan Radecki has also some good stuff online and in print about it. I’ve even got my own compendium on it.

When I heard IST-3 was underway and almost ready to report I was quite excited to see someone finally answering the question in a rigorous way – do lytics in acute stroke improve outcomes? The trial that is still cited is the original NINDS trial. It showed a benefit but it was small (comparatively) and there were baseline differences between the groups that may have biased the trial in favour of tPA. This could have been answered by repeating the trial and replicating the results (a fairly common practice). This has never been done and unfortunately IST-3 is not the one to do it either. Now that’s hardly surprising – it was never the question the authors set out to answer.

If you don’t fancy reading the more detailed analysis below here’s the three major problems my point of view.

- this is an open label trial – It was blinded at assessment but in hospital following treatment everyone knew who got tPA and who didn’t and they were treated differently. This is a potential source of bias

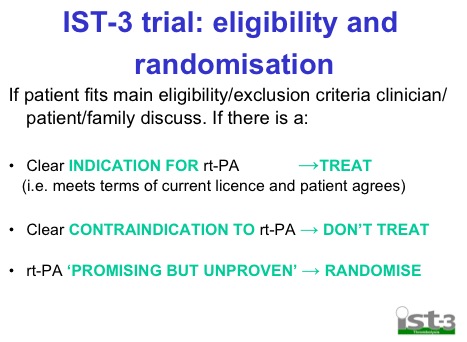

- it only randomised people currently outside the licence for tPA so it’s testing an entirely different bunch from NINDS. See here for which patients were randomised.

- it was a negative trial by its primary outcome. Something the authors don’t acknowledge in the conclusion in the abstract.

There are lots of other problems that I’ve highlighted below. I’d be interested in your thoughts.

METHODS

- multicentre international RCT

- a pilot phase (<10% total) was blinded and then in the main trial it was open label. They don’t explain why the main trial was open label but presumably it’s cheaper and easier to do.

- Randomised on basis of uncertainty principle. Basically if you’re unsure whether or not you should give it based on current guidelines then randomise

- all kinds of follow-up but mainly via GP or phone or mailed questionnaire

- originally planned for 6000 but recruitment insufficient so recalculated their power and changed the statistical plan.

- realised that there were big differences in the sub-groups at baseline (mainly on time and stroke severity) and had to apply logistic regression to adjust for them. Seeing as the only +ve results in the trial were in the sub-groups it makes me further question their significance if they were adjusted to compensate for base-line imbalances.

RESULTS

- 3000 over 10 years (which is very slow) 300/yr split between 150 centres means 2/yr/centre

- half over 80 years old

- virtually all outside the current european licence (which is the point of the trial)

- mainly treated at 4.2hrs

- pts who got tPA more likely to go to HDU (24%v17%) than those who didn’t. For this you could perhaps make the assumption that pts who got tPA got better nursing care…

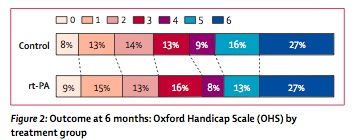

- big spike in early deaths (11% v 7%) but then improved by 6 months (16% v 20%). Overall mortality was identical at 6 months

- found a 2% benefit in primary outcome (alive and independent, 35% v 37%) at 6 months. A difference this small of course did not reach statistical significance. You could call this an NNT of 50 if it was real.

- significant ICH 7% v 1%

- oddly an increase in fatal swelling (odd because if tPA works then the infarct would be smaller and the swelling would be less) of infarcts in tPA group of 47 pts v 25 pts. This is played down as inconsistent with prior studies in the paper UPDATE: it was pointed out to me by a fine neurologist that when you lyse the clot you get reperfusion oedema so this is actually a sign the tPA does breakdown clot. It makes sense. It’s still a problem if the reperfusion oedema kills people, but it’s not oedema simply from a big infarct.

- they have a whole ream of things in the forest plot of secondary outcomes (these are the adjusted ones) and only one approaches significance – age >80 yrs. Unfortunately as Ryan points out – if it’s better for those greater than 80 then it’s worse for those <80 – which is the precise opposite of prior trials.

Below is a video of the lead author talking about the results if you’re interested

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E9oRXu2ORCY&feature=g-hist

The paper itself lives here

In the same issue the same authors have published an updated systematic review and meta-analysis that now includes these results. One of the concerns that has been pointed out before is perhaps this heterogeneous data set (now up to 12 very differently ran trials) aren’t actually appropriate to meta-analyse.

There’s a glowing editorial about the trial that makes the slightly odd and even reckless statement that:

Every stroke patient should therefore be classed as a candidate for thrombolysis

This seems a little bit of a stretch seeing as the IST-3 trial used these criteria and excluded lots of pts:

My suspicion as always, is that tPA does work for some patients with stroke, but certainly not all and until we can pick out the ones who benefit then I suspect that we shouldn’t have adopted this as wholeheartedly as we already have.

UPDATE – if you look at page 4 of the supplementary appendix there’s a list of the drug treatments that varied between the 2 groups. The two groups were treated differently

References:

The RCTs

- Intravenous desmoteplase in patients with acute ischaemic stroke selected by MRI perfusion-diffusion weighted imaging or perfusion CT (DIAS-2): a prospective, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet Neurology 2009 Feb.;8(2):141–150. PMCID 2730486

- Effects of alteplase beyond 3 h after stroke in the Echoplanar Imaging Thrombolytic Evaluation Trial (EPITHET): a placebo-controlled randomised trial. Lancet Neurology 2008 Apr.;7(4):299–309.PMID 18296121

- Randomised controlled trial of streptokinase, aspirin, and combination of both in treatment of acute ischaemic stroke. Multicentre Acute Stroke Trial–Italy (MAST-I) Group. The Lancet 1995 Dec.;346(8989):1509 -1514. PMID: 7491044

- Thrombolytic therapy with streptokinase in acute ischemic stroke. The Multicenter Acute Stroke Trial–Europe Study Group (MAST-E). N Engl J Med 1996 Jul.;335(3):145–150. PMID: 8657211

- Streptokinase for acute ischemic stroke with relationship to time of administration: Australian Streptokinase (ASK) Trial Study Group. JAMA 1996 Sep.;276(12):961–966. PMID: 8805730

- Recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (Alteplase) for ischemic stroke 3 to 5 hours after symptom onset. The ATLANTIS (B) Study: a randomized controlled trial. Alteplase Thrombolysis for Acute Noninterventional Therapy in Ischemic Stroke. JAMA 1999 Dec.;282(21):2019–2026. PMID: 10591384

- The rtPA (alteplase) 0- to 6-hour acute stroke trial, part A (A0276g) : results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. Thromblytic therapy in acute ischemic stroke study investigators.(ATLANTIS A) Stroke 2000 Apr.;31(4):811–816. PMID 10753980

- Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group (NINDS). N Engl J Med 1995 Dec.;333(24):1581–1587. PMID: 7477192

- Intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute hemispheric stroke. The European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS). JAMA 1995 Oct.;274(13):1017–1025.1. PMID: 7563451

- Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of thrombolytic therapy with intravenous alteplase in acute ischaemic stroke (ECASS II). Second European-Australasian Acute Stroke Study Investigators. The Lancet 1998 Oct.;352(9136):1245–1251. PMID: 9788453

- Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke (ECASS III). N Engl J Med 2008 Sep.;359(13):1317–1329. PMID: 18815396

- The IST-3 collaborative group. The benefits and harms of intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator within 6 h of acute ischaemic stroke (the third international stroke trial [IST-3]): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012 May 23. PMID: 22632908

Some of the #FOAMed resources on lytic for stroke debate:

LITFL – CCC Stroke Thrombolysis

LITFL – Michelle Johnston on tPA for stroke

EMCrit Cage Match – Jagoda v Swaminathan

Busting the Clotbusters – Domhnall Brannigan

SMART EM – thrombolytics for stroke

Oregon Stoke Network debate: Jerry Hoffman and Greg Albers [2hr video]

Hey Andy, was just re-reading your awesome summary on lysis and nipped over to the IST3 website and noticed one small detail which interested (concerned?) me. I had a look at the recruitment and randomisation process, and although at face value it seems useful that current off-label “indications” would be included, I wondered somewhat how they would analyse the data from those they state as having a “clear indication” for tPA. The value of the trial could hinge on how they incorporate the data from this group… Just a thought, care to comment? Will DM you a screen grab on the bit I mean on Twitter if I can.

Good spot Domhnall, I didn’t read their methods in that much detail. I thought they were doing a full double blind RCT of all comer stroke pts but they’re clearly not

I feel a new post coming on…

Pingback: Some updates on IST-3 | Emergency Medicine Ireland

Pingback: On IST-3 and why we still don’t have the answer we were looking for… |

Pingback: What am I missing here? « DrGDH

Pingback: IST-3 and thrombolysis in Stroke

Pingback: Neurology Resources for Medical Students (1/2) - Manu et Corde

Pingback: On IST-3 and why we still don't have the answer we were looking for... - Emergency Medicine Ireland

Pingback: Some updates on IST-3 - Emergency Medicine Ireland

Pingback: Thrombolysis for stroke head to head in the BMJ - Emergency Medicine Ireland

Pingback: The LITFL Review 027 - Life in the FastLane Medical Blog

Pingback: IST-3 and thrombolysis in Stroke

Pingback: JC: Time is brain...., calling #FOAMagitators. St.Emlyn's - St Emlyns

Pingback: Vem ska man tro på? Om trombolys vid stroke. | akut eftertanke

Pingback: The Use of Thrombolysis as a Treatment for Acute Stroke

Pingback: Sweets » Blog Archive Trombolys vid stroke - finns det skäl att vara skeptisk? » Sweets

Pingback: Stroke Thrombolysis • LITFL

Pingback: IST-3 and thrombolysis in Stroke • LITFL • Schrödinger’s Fence

Pingback: The Use of Thrombolysis as a Treatment for Acute Stroke • LITFL