I’m back at the European Society for Emergency Meeting for another couple of talks (older ones can be found here , here and here…).

I have the luxury of getting to pick my topics which gives me the opportunity to express my love of the uncommon but important in emergency medicine.

Cerebral venous thrombosis, or whatever term you wish to call it by, is one of those great and rare diagnoses. It has a myriad of presentations from the ambulatory to the super sick and is frequently missed or delayed in diagnosis.

This is actually something i covered on the AFEM podcast years ago and is worth watching for a quick review

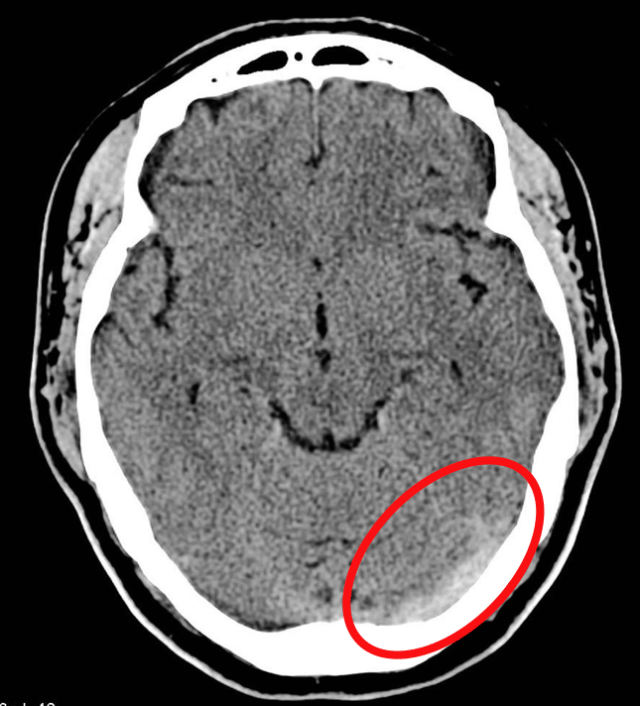

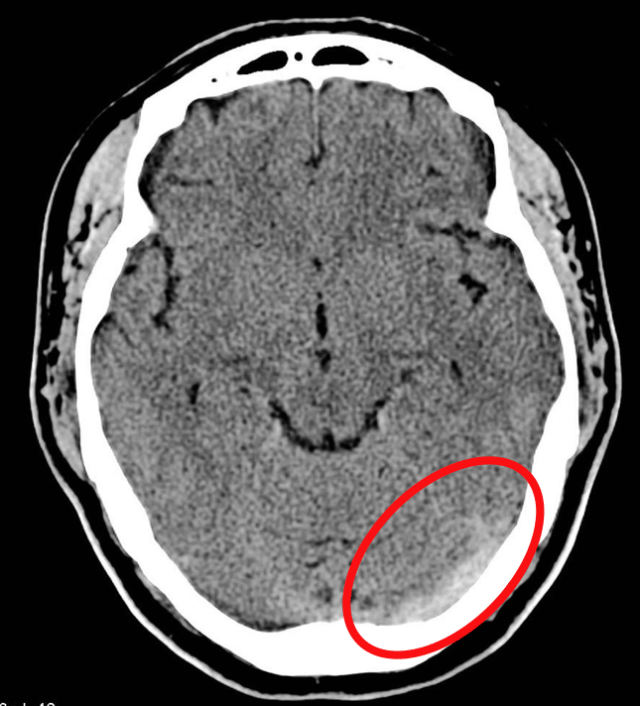

The anatomy here dictates the clinical findings. Non arterial distribution bleeding is a big clue. Most SAH comes from the circle of willis so expect to it there. So if you see blood lying along side the falx cerebri then it may well be venous bleeding from high pressure in the sagittal sinus. In this case the blood is along the left transverse sinus

Case courtesy of A.Prof Frank Gaillard, Radiopaedia.org. From the case rID: 5522

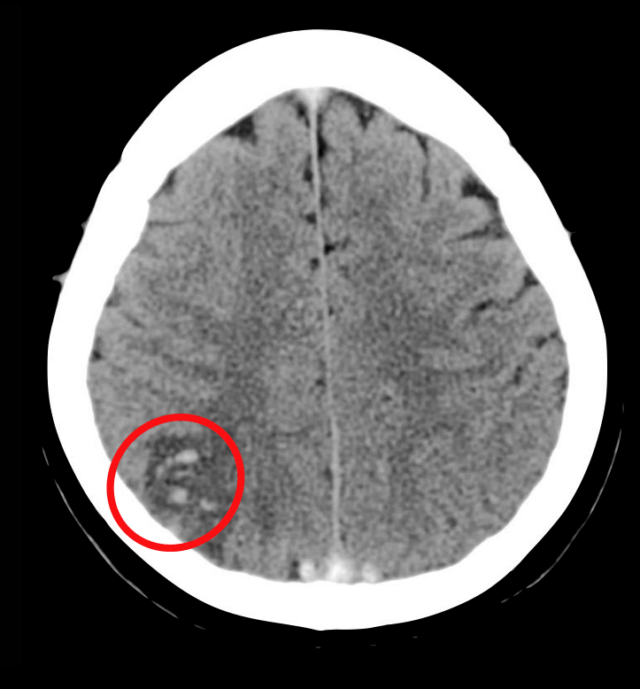

You may see non arterial territory infarcts as well. As flow from the cortical veins backs up you can get venous infarcts like this right parietal lobe infarct here.

Case courtesy of A.Prof Frank Gaillard, Radiopaedia.org. From the case rID: 5522

this is a rare disease. I’m still in the single figures for the number i’ve seen personally over 15 years. You will see more strokes, migraines and even sub arachnoid haemorrhages than this.

it’s counted as a stroke but it’s <1% of strokes.

though it remains really important to be on our differential as it has a specific diagnostic and management pathway that differs from many of the other causes of stroke. they also tend to be much younger patients without the long comorbidity list of the typical stroke patient

most people seem to forget this but for something like PE, up to 50% have no discernible risk factor for thrombosis in the lungs.

in CVST it seems from the data we have that most people will have some risk factor identified but it’s clear that it is possible to have CVST without any identifiable risk factors. (UTD quotes 85% have a RF)

there’s a female predominance of 3:1 likely reflecting the hormonal risks surrounding OCP and pregnancy

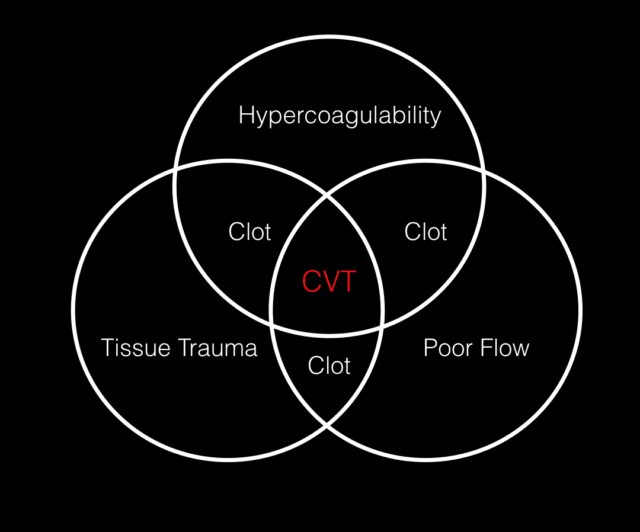

most of the RF are the same as for VTE anywhere else. it’s the venn diagram of hyper coagulability, reduced flow and endothelial trauma

for hyper coagulability think OCP use, pregnancy and particularly the post partum period. things like lupus or factor V leiden also in there.

in terms of tissue trauma or poor flow think recent surgery or even recent concussion type injuries has been reported. the nasty ENT infections show up here too – the invasive mastoiditis sinus infection has been implicated also.

First division is sick/not sick. We’re typically pretty good at this. However we make different kinds of diagnostic errors with each different group.

CVT can present with a number of syndromes. In the lecture I gave 4 case examples:

- Case 1: The seizure

- 30 year old female 2 weeks post part from a normal delivery of a beautiful baby girl.

- she arrives in status epilepticus, quickly settled with some bentos. you notice she’s not moving her right arm. Her CT shows a parietal haemorrhage

Case courtesy of A.Prof Frank Gaillard, Radiopaedia.org. From the case rID: 5522

- Case 2: The Headache

- in ambulatory care you have a young female with no past history with a severe, thunderclap headache. She’s on no meds apart from the OCP. Your CT looks OK, it’s within 3 hrs. Should you just stop there. Does she need the LP? Something in the back of your head (no pun intended…) tells you you’re missing something

Case courtesy of Dr Andrew Dixon, Radiopaedia.org. From the case rID: 32376

- Case 3: The head injury

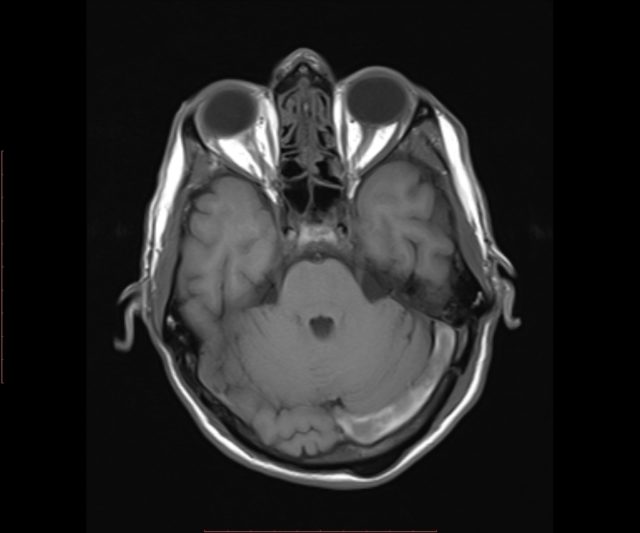

a 40 year old man presents a week following a head injury and concussion. His CT showed a linear unrepressed skull fracture and he’s on no anticoagulants. He’s now had increasing right sided weakness over 2 days and worsening of his headache from the head injury. You skip the repeat CT and go straight to MR and you see this in the left cerebellum.

Case courtesy of Dr Hidayatullah Hamidi, Radiopaedia.org. From the case rID: 52813

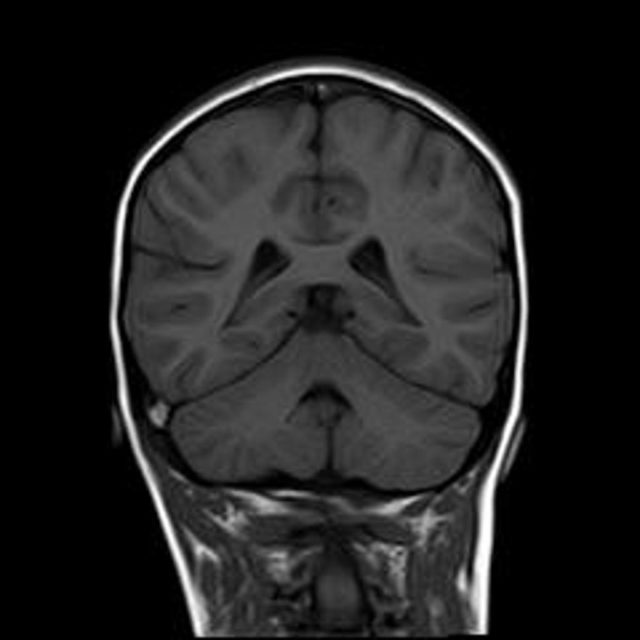

- Case 4: The infection

This young male attends with a recurrent and worsening right ear pain and discharge. He had surgery a month ago as part of treatment for mastoiditis. He now has numbness in his right hand and difficulty grasping his keys.

Case courtesy of Dr Dalia Ibrahim, Radiopaedia.org. From the case rID: 28971

These cases form a wide range of presentations from the super sick patient to those headaches in your ambulatory care area.

These guys will all be getting imaging and lots of supportive care. We do our ABCs and get a scan and see infarct or blood and that’s the end of our diagnostic reasoning process delaying what might be definitive care and imaging.

the bleeding we’re going to get in CVST is venous typically and so you might see sub arch blood in an unusual place like up at the superior part of the brain along the sagittal sinus. arterial aneurysmal blood should be around the circle of willis and the MCA.

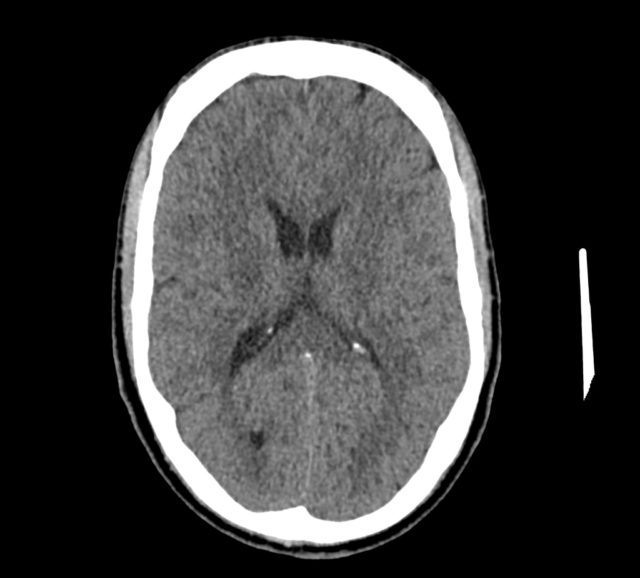

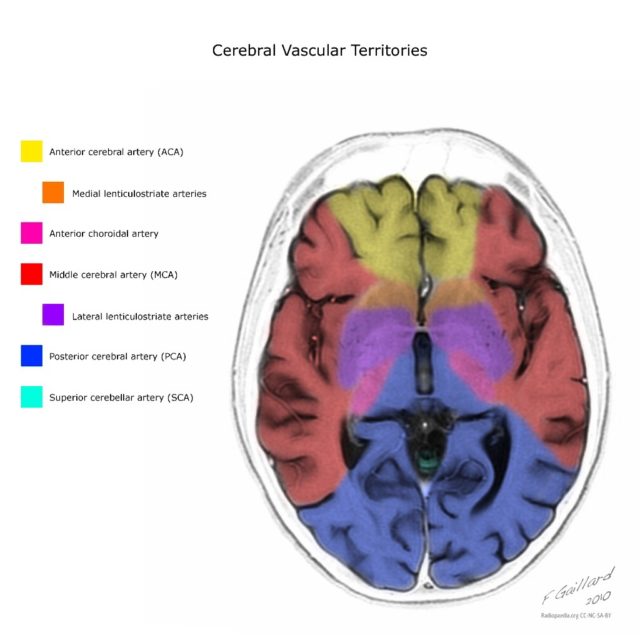

if we see infarct we think stroke but stroke is again an arterial disease and we expect to be in typical arterial territories as shown here.

Case courtesy of A.Prof Frank Gaillard, Radiopaedia.org. From the case rID: 10814

Remember the infarcts in CVST are venous typically lying adjacent to the venous drainage and cross arterial territories.

If you have a good radiologist then they’ll probably pick up on this but we rarely give them a good enough clinical picture to do their job properly so go and talk to them and discuss the case

The typical presentation here is one of severe headache and rightly so top of our list is SAH and we focus our work up on that.

We can make the mistake of going down the routine ED headache pathway to rule out SAH. Either doing the CT early and rightly ruling out SAH and missing the CVT. Or we do the CT and LP but miss or ignore the key features on the LP.

It’s not that the work up we’re doing in the either the sick or not sick patients is wrong it’s just that we don’t keep our differential broad enough to go the extra few steps to make the diagnosis

In terms of LP there’s a few features that might point it out. remember in this not sick patient you’re not expecting the LP to be abnormal, you’re not expecting meningitis here. you’re really doing it as part of your SAH work up. a high opening pressure , a raised lymphocyte pleocytosis and a high protein level are present in various combinations in 50% of CVST

if you’re used to doing your LPs sitting (which i generally find easier) then you’re missing out on opening pressures. get out your manometer and measure the pressure. a high pressure is considered >20cm of CSF.

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (formerly pseudotumour) is the main differential with a conscious patient with normal CT and high pressure.

Incidentally if it’s low (<6) then you might be looking at a CSF leak headache.

none of these LP features are especially specific for CVST. all they are are prompts to consider expanding your differential.

Jeff Perry’s work in SAH has been brilliant and I think rule out SAH with an early CT is perfectly reasonable. But we’re still not off the hook for all the other causes of SAH and we have to maintain that differential diagnosis.

you might get lucky and have some findings on the non con CT scan. remember the hyper dense MCA sign that you see in stroke? this is analogous to this for veins. Acute thrombosis can appear hyperdense on CT. Here on the left you have some hyper density of one of the cortical veins and the post part of the superior sagittal sinus.

Case courtesy of A.Prof Frank Gaillard, Radiopaedia.org. From the case rID: 4408

Case courtesy of A.Prof Frank Gaillard, Radiopaedia.org. From the case rID: 4408

if you add some contrast and time it right you can get a venogram and here we have the “empty delta sign” with contrast surrounding a clot in the sagittal sinus

In terms of CTV v MRV the AHA guidance on this views CTV and MRV as equivalent. MRI is probably a little better but honestly this will come down to whatever your radiologists are happy with so don’t get too worried about it.

Should we used dimer as part of our diagnostic work up?

There’s not much out there on it. there have been some small studies but given how badly we’ve used dimer in VTE, I doubt it can be used in a disease state with even more heterogeneity in presentation than PE.

We do all the usual supportive care but definitive treatment (we think) is anticoagulation

most of our job here is considering the diagnosis early and getting the right test. Once the diagnosis made the clear consensus is that they all need anticoagulated.

there are some studies of interventional clot lysis but they’re small and so far no joy. the mainstay of care remains supportive and anticoagulation

the observational data here is clear as far as observational data goes. but there are two small RCTs but both have big issues

everyone agrees anticoagulation is the way to go. there is little agreement on quite how to do it. In reality most of the options we have from IV heparin to warfarin are all reasonable but it’s low level evidence. DOACs may well be OK, but there’s no data that i could find.

lots of these patients will have bleeding visible on CT. Surely we don’t anticoagulant them? Well the answer is yes we do and the guidelines all support that

Charlotte Davies on RCEM Learning

1. Benabu Y, Mark L, Daniel S, Glikstein R. Cerebral venous thrombosis presenting with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Case report and review. Am J Emerg Med. 2009 Jan;27(1):96–106.

2. Canhao P, Ferro JM, Lindgren AG, Bousser MG, Stam J, Barinagarrementeria F, et al. Causes and Predictors of Death in Cerebral Venous Thrombosis. Stroke. 2005 Jul 27;36(8):1720–5.

3. Ducros A, Bousser M-G. Thunderclap headache. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2013;346:e8557.

4. Evans RW. Migraine Mimics. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 2015 Feb 6;55(2):313–22.

5. Ferro JM. Prognosis of Cerebral Vein and Dural Sinus Thrombosis: Results of the International Study on Cerebral Vein and Dural Sinus Thrombosis (ISCVT). Stroke. 2004 Feb 12;35(3):664–70.

6. Fischer C, Goldstein J, Edlow J. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in the emergency department: retrospective analysis of 17 cases and review of the literature. 2010 Feb;38(2):140–7.

7. Long B, Koyfman A, Runyon MS. Cerebral Venous Thrombosis: A Challenging Neurologic Diagnosis. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2017 Nov;35(4):869–78.

8. MD JRP, MD JHK. Basic Neuroanatomy and Stroke Syndromes. Emerg Med Clin North Am. Elsevier Inc; 2012 Aug 1;30(3):601–15.

9. Sayer D, Bloom B, Fernando K, Jones S, Benton S, Dev S, et al. An Observational Study of 2,248 Patients Presenting With Headache, Suggestive of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage, Who Received Lumbar Punctures Following Normal Computed Tomography of the Head. Panagos PD, editor. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2015 Oct 19;22(11):1267–73.

10. Stella CL, Jodicke CD, How HY, Harkness UF, Sibai BM. Postpartum headache: is your work-up complete? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Apr;196(4):318.e1–7.

11. Tabatabai RR, Swadron SP. Headache in the Emergency Department: Avoiding Misdiagnosis of Dangerous Secondary Causes. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2016 Nov;34(4):695–716.

12. Thomas G DeLoughery MD F. Venous Thrombotic Emergencies. Emerg Med Clin North Am. Elsevier Ltd; 2009 Aug 1;27(3):445–58.

13. Wilson MH. Monro-Kellie 2.0: The dynamic vascular and venous pathophysiological components of intracranial pressure. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. SAGE Publications; 2016 May 12;:1–13.

Pingback: St.Emlyn's at #EuSEM18 - Day 4 - St.Emlyn's