It’s 2am, you’re just catching up on the waiting room an things are beginning to settle when one of the many bat phones in the department rings to alert you to the imminent arrival of a 75 year old man from a house fire. No details but he’s sick as.

[peekaboo_link name=”What runs through your head at this point”]What runs through your head at this point[/peekaboo_link]

[peekaboo_content name=”What runs through your head at this point”]

Hopefully a number of things

Airway

- a burnt, oedematous airway would be a nightmare to intubate. Do you know where your advanced airway equipment is? What’s your rescue device? Is it time to think CricCon?

- Smoke inhalation. This needs emphasised – this is the major cause of death in house fires NOT burns

- if these are full thickness and circumferential then you just might need your scalpel

- if there’s significant BSA involved you’re going to need lots of IV fluids. Something that’s difficult to do

- When people are in house fires and trapped on the first floor what do they do? Jump out. That’s what I plan on doing instead of being burnt to death

- Think C-spine, think calcanei, think head trauma

[/peekaboo_content]

[peekaboo_link name=”Whats the deal with CO poisoning”]Whats the deal with CO poisoning[/peekaboo_link]

[peekaboo_content name=”Whats the deal with CO poisoning”]

As mentioned smoke inhalation is the major killer in house fires NOT the burns. It’s easy to get distracted by impressive looking major burns and forget about the invisible little toxicites killing your patient.

There are 3 main things I think about with smoke inhalation:

- Direct airway injury

- heat applied to the upper airway can cause oedema and ultimately airway obstruction manifested subtly with hoarse voice (ask them to count to 10 to see if they’re hoarse by the time they reach 10), carbonaceous deposits in the mouth and more obviously with stridor.

- Remember that air is a fairly poor conductor of heat so it takes a lot of heat to burn the airway. Steam is thought to be a higher risk for this.

- The airways below the cords can also be damaged but this is more of a complicated process involving debris, de-epithelisation and shedding of the necrotic lining of the airways with the development of ARDS and all that.

- Cyanide Toxicity

- Cyanide is produced with the combustion of multiple materials but classically these are thought to be upholstery and plastics.

- It’s hard to know how common this is as a cyanide level will come back shortly after your patients funeral so if you’re going to treat it then you’ll have to treat on suspicion

- Be suspicious if

- super sick

- seizures

- high lactate/severe acidosis

- Treat with (controversial)

- there’s lots of ways to do this with the drugs which deserves a post of its own but if I ever treat it I’ll be reaching for the hyroxycobalamin

- Carbon Monoxide Toxicity

The last thing to mention is good old fashioned asphyxia. If all the oxy is being used for combustion then chances are the atmospheric FiO2 is < 0.21.

[/peekaboo_content]

[peekaboo_link name=”Want to know more on Carbon Monoxide (CO) Toxicity”]Want to know more on Carbon Monoxide (CO) Toxicity[/peekaboo_link]

[peekaboo_content name=”Want to know more on Carbon Monoxide (CO) Toxicity”]

Carbon monoxide is produced whenever there is incomplete combustion of hydrocarbons. In house fires there’s frequently more burning that there is oxygen so lots of CO is produced. It is thought to be the commonest cause of death in house fires, but also a significant issue in faulty boilers and furnaces.

[/peekaboo_content]

[peekaboo_link name=”How does CO make you sick”]How does CO make you sick[/peekaboo_link]

[peekaboo_content name=”How does CO make you sick”]

Ultimately we all die of lack of oxidative metabolism. Be this shunt from pneumonia or a metabolic poison like cyanide. They all have slightly different mechanisms and points where they disrupt tissue oxygenation.

CO is very keen to make life long friends with your haemoglobin. (binds to Hb with 240 times the affinity of O2) Your haemoglobin should really know better but what do you do…

It also binds to myoglobin and has effects on mitochondrial function too. The functional anemia described below does not explain why CO is so deadly

CO is rapidly transferred across your alveoli to the bloodstream where it binds avidly to Hb in your RBCs blocking all the binding sites that Oxygen is used to binding to.

This leads to a sort of functional anaemia. If All your Hb is saturated with Oxygen your SaO2 will be 100%. If all half your Hb is saturated with CO then your Sa02 will only be 50%.

Remember that the best way to move oxygen around your body and deliver it to the tissues is with OxyHb. the Pao2 you measure in your blood gas is only dissolved oxygen which contributes much less to tissue oxygenation.

[/peekaboo_content]

[peekaboo_link name=”So how do I tell if someone as CO poisoning”]So how do I tell if someone as CO poisoning[/peekaboo_link]

[peekaboo_content name=”So how do I tell if someone as CO poisoning”]

With your local friendly blood gas analyser.

A decent blood gas machine with have a thing called a co-oximiter in it which will be able to tell you very accurately the binding states of your Hb.

You may think that Hb can be either OxyHb or DeOxyHb but as mentioned your Hb is a promiscuous little bugger and will happily run off and form CarboxyHb and MetHb given the first opportunity.

Your Sats probes (Sp02) can tell the difference between OxyHb and DeOxyHb. It does this by measuring two different frequencies of infra red light (940nm and 660nm if you’re interested. Oh you weren’t…). The two different types of Hb absorb different frequencies of light.

Your standard sats probe will not be able to tell the difference between OxyHb and CarboxyHb and will tend to float somewhere around the 80s.

There are fancy commercially available probes that will use frequencies appropriate for MetHb and COHb but they’re not common and are used for triaging house fire victims at house fires and assessing exposure in fire fighters.

The co-oximeter on your local friendly blood gas machine will help you out here.

Just remember that your PaO2 is a measure of dissolved oxy in the blood and will likely be fairly normal. We’re not interested in dissolved O2.

[/peekaboo_content]

[peekaboo_link name=”Do I need an arterial sample”]Do I need an arterial sample[/peekaboo_link]

[peekaboo_content name=”Do I need an arterial sample”]

What do you think? The answer to this question (unless you’re the admitting medical reg) will always be “venous is just fine”. The COHb is just circulating around there from arterial to venous and back again so don’t stress it. (reference)

[/peekaboo_content]

[peekaboo_link name=”How do I treat it”]How do I treat it[/peekaboo_link]

[peekaboo_content name=”How do I treat it”]

In many ways this is easy. Oxygen and lots of it.

- the haf-life of COHb in an FiO2 of 0.21 is 300 minutes

- the half-life of COHb in an FiO2 of 1.0 is 60-90 minutes

Practically you need to think about this. The old “100% rebreather” will not come anywhere near a 100%. The flow rates of someone spontaneously breathing will draw in room air around the mask.

And if this doesn’t work then they’re heading for an ETT.

[/peekaboo_content]

[peekaboo_link name=”Hyperbaric”]Hyperbaric[/peekaboo_link]

[peekaboo_content name=”Hyperbaric”]

Now we’re hitting the controversy. There’s good science (if not good evidence) behind the idea that putting someone with CO poisoning in a chamber should help fix them. But there are a few problems:

- the evidence is shaky

- even if it worked putting a sick, ventilated, seizing patient in a chamber is a nightmare of epic proportions

[/peekaboo_content]

[peekaboo_link name=”Case Outcome”]Case Outcome[/peekaboo_link]

[peekaboo_content name=”Case Outcome”]

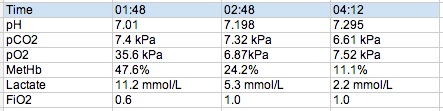

Our gentleman is intubated following the first ABG shown below and rapidly becomes fairly tricky to oxygenate despite the usual tricks. The COHb level drops rapidly and a bronch in the ICU shows lots of carbonaceous debris and sloughing in the bronchial tree.

[/peekaboo_content]

[peekaboo_link name=”Lastly”]Lastly[/peekaboo_link]

[peekaboo_content name=”Lastly”]

I realised I’d done a presentation on this (and cyanide) before so here it is in all it’s #FOAMed, slideshare glory…

And of course as soon as I finish writing this I realise Chris over at LITFL already has a great post on it from a few years back.

[/peekaboo_content]

Hey Andy,

Great summary, particularly in the day that’s in it. Hopefully Pun won’t need to quickly read this tonight!

Just wondering, did this man get transferred to our friendly burns centre?

No, went upstairs to ICU. There were no burns just the inhalational injury.

Nice case Andy! Just about the sats….surely the sats (if the oxyHb and carboxyHb are indistinguishable on the oximeter) should be normal, unless there was hypoxia from something else like a low Fi02 , bronchospasm. or airway obstruction.

Cheers Vinnie

The blood gas machine measures the different hb using co oximetry. It can tell the difference between COHb and oxyHb.

The sats probe can only tell the difference between oxyHb and deoxyHb.

So effectively this pt had carboxyhb of 47% and oxyHb of 53%. The sats probe was reading sats in the 80s.

I’d add that you shuold probably give sodium thiosulfate if cyanide poisoning is suspected with hydroxocobalamin. The thiosulfate takes cyanide and makes thiocyanide which is excreted in the urine and plays no role in worsening a patient’s likely concurrent metHb like amyl or sodium nitrite.

fair point – it’s the metHb inducers that I really don’t like!

You can get to 100% FiO2 with pseudo-NRB by going past the last past the 15L marker to up to 30-60L/min. At least thats what that Levitan/Weingart Annals article stated.

But most oxygen meters only go up to 15/min. A portable vent on 100% O2 with a well fitted mask will allow you flow rates over 100L/min

Pingback: Rescatado del incendio: ¿qué viene después? | Reanimación.net

Pingback: Carbon monoxide toxicity | Emergency Nursing | Scoop.it

Pingback: The LITFL Review 025 - Life in the Fast Lane medical education blog

Pingback: TOXICOS/QUEMADOS – Rescatado del incendio: ¿qué viene después? |

Pingback: The LITFL Review 082