Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 4:57 — 7.1MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | RSS

Welcome back to the tasty morsels of critical care podcast.

This week we’re looking at the other ACS, the surgical ACS, the old abdominal compartment syndrome. This is common, especially in the surgical population and does not always immediately jump to the front of our cerebral hemispheres when it should do. Believe it or not there is a World Society of abdominal compartment syndrome that has been on the go since 2004 and you can become a life time member for free if you want.

They even have a set of consensus guidelines published back in 2013 that provide a wonderful template for an exam answer even if they aren’t supported by the highest level evidence.

So a few basics to start with. The measurement should be done by attaching a properly calibrated and zeroed pressure transducer to a port on the urinary catheter following an installation of no more than 25mls sterile saline in the supine position at end expiration. This is considered the reference standard though I do remember concocting some Mcgyver style manometer on a needle thing years and years ago.

There is a grading system for the degree of abdominal hypertension with the higher grades being higher pressures. Important to note that these pressures are in mmHg and if you’re using some old school manometry method then you may need to use the appropriate conversion factor. A normal intra-abdominal pressure is usually in the 5-7mmHg range in the critically ill as a reference.

Intra-abdominal hypertension is one thing and it is worth looking for but it is key to note that a high pressure on its own does not equal ACS. To be ACS you need a pressure >20mmHg and associated organ dysfunction with a good example or organ dysfunction being AKI.

Finally in terms of definitions you can split ACS into primary and secondary with primary being the intra-abdominal catastrophe where the surgeons find it hard to get the wound closed. Secondary causes are more likely to be related to medical illness with overly aggressive fluid resuscitation (otherwise known as iatrogenic salt water drowning) leading to oedematous abdominal structures and high pressures.

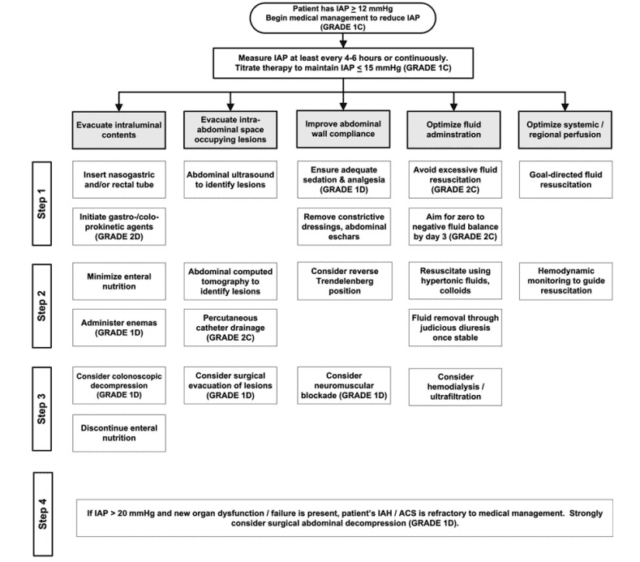

Once the diagnosis is made then the guideline has split the interventions into 5 categories summarised neatly in a table reproduced in the show notes. I’m not suggesting these are the ideal way to manage ACS but they are certainly reproducible in a viva or written type exam and certainly covers all the bases.

You can split up the interventions and categories as follows

- evacuate the intraluminal contents. NG tubes on drainage, enemas and laxatives to clear things out from the bottom end. Removing contents from the abdominal cavity will lower the pressure. Colonic decompression with endoscopy is at the extreme end of this and I’ll confess I’d probably plump for neostigmine well before that.

- evacuate intra-abdominal collections. If there’s a 10cm rim enhancing lesion on the CT 10 days post surgery then that needs dealt with not just for source control reasons but also as another adjunct to lowering the pressure

- improve the abdominal compliance. This is something we’re kind of used to in intensive care as it involves deep sedation and even paralysis. If muscular tone is worsening things then get rid of it

- optimise fluid resuscitation. Time to unleash your diuresis jedi or even maximize your ultrafiltration and get the patient in a -ve balance.

- optimise perfusion. here they move into the concept of abdominal perfusion pressure which they define like CPP as MAP-Abdominal pressure.

These are all very nice and should all be reflected upon and followed when appropriate in your ACS patient. But it is critical that you don’t forget the all important step that comes at the bottom of this algorithm – if all else fails open the abdomen. In reality I’ve only ever seen this done in surgical cases where the belly is already open as part of the surgery and like a middle aged man trying to fit into an old suit it turns out you just can’t squeeze all the contents back in. One of the commonest examples would be the open emergency AAA repair where the large retroperitoneal haematoma just makes it too hard to close fascia and skin – they often return with the abdomen still open and I give thanks to the surgical gods above that they have done so. In the era of the EVAR these patients are much more at risk of ACS as the belly never gets opened.

References:

Kirkpatrick et al, Intra-abdominal hypertension and the abdominal compartment syndrome: updated consensus definitions and clinical practice guidelines from the World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. Intensive Care Medicine 2013