This is a series of posts where I’m trying to transfer my anatomy lectures to a blog format, with emphasis on the clinically relevant points.

Images are mainly from the 1918 Grays, freely available and out of copyright here. Forgive the out of date nomenclature…

The shoulder:

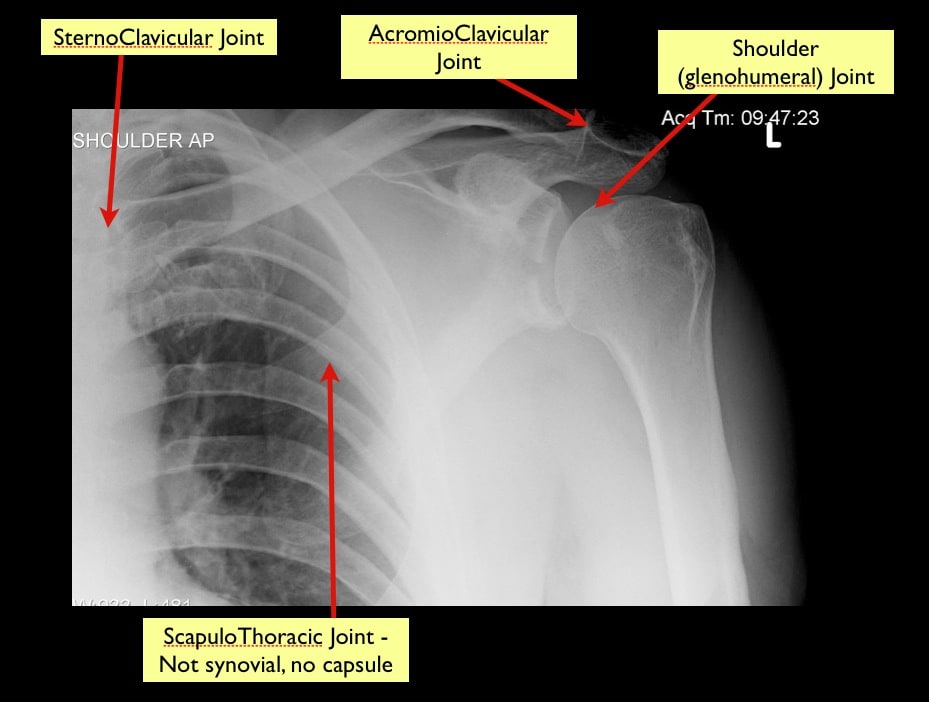

You can describe 4 different joints involved in shoulder movement:

- In something complex like shoulder abduction, all 4 joints come into play; this is incredibly important to realise both for pathology and even in terms of examination of what’s normal.

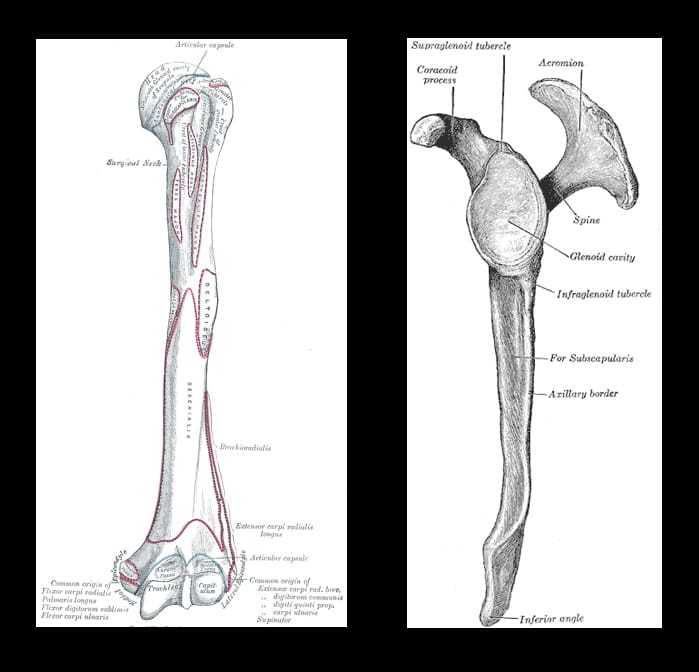

- The exceptional thing about the glenohumeral joint is its exceptional range of movement, able to cope with such vital human behaviours as climbing trees to run away from bears, to putting on a bra.

- It is often described as having 3 degrees of freedom (which is different from 6 degrees of Kevin Bacon) meaning there is movement along 3 axes. In terms of movements this means flexion/extension, abduction/adduction and internal/external rotation.

- The shape of the humeral head and the shallow glenoid fossa allow this range of movement. It also leads to its frequent injury and dislocation

What functions to stop the humeral head falling out of the glenoid?

- Static

- Intrinsic Ligaments

- Extrinsic Ligaments

- Dynamic

- rotator cuff

- long head of biceps

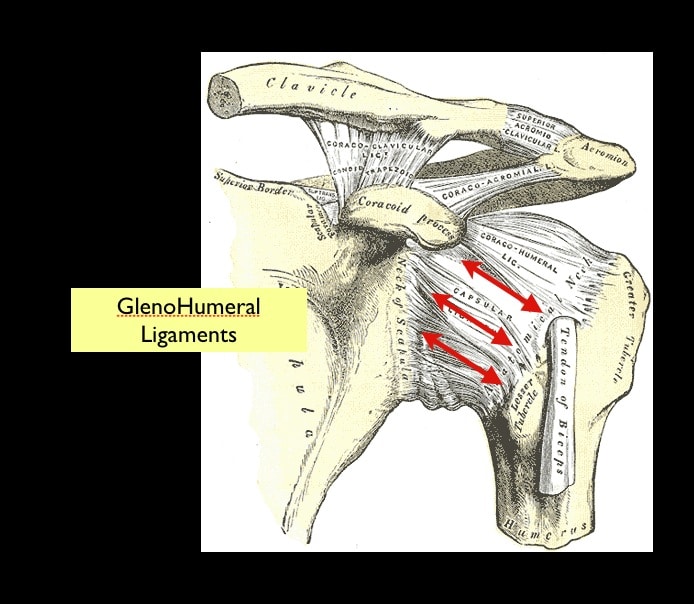

- There are 3 “intrinsic” (meaning thickenings of the capsule itself) glenohumeral ligaments, helpfully named sup, mid and inf.

- All 3 lie in the anterior capsule

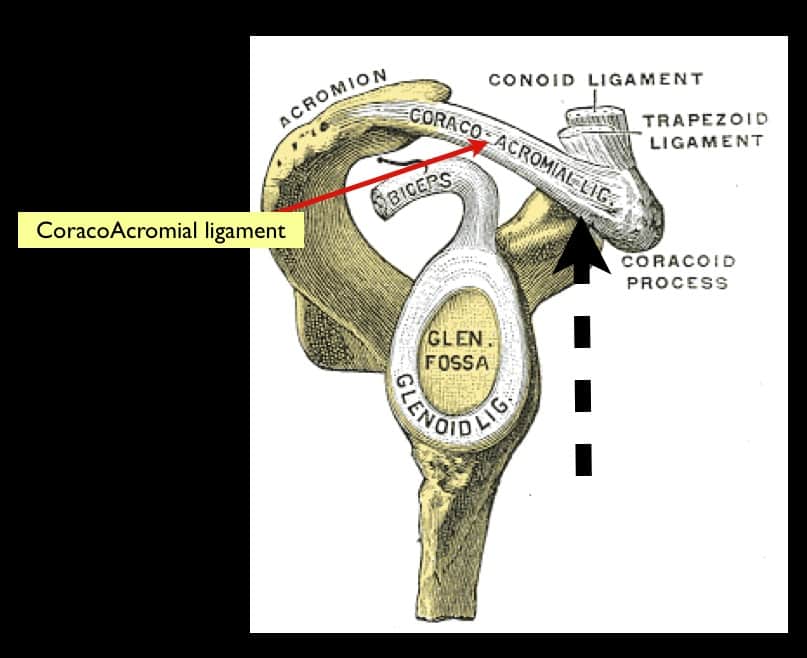

- Note the coracoacromial ligament has nothing to do with the AC joint injuries

Dynamic Stability

- largely of the rotator cuff, a group of 4 muscles with attachments into the capsule and all around the humeral head.

- Their job is to pull the humeral head into the fossa no matter what position the humerus is in

- One attached anterior (subscapularis), one on top (supraspinatus) and two posterior (teres minor and infraspinatus)

Here’s a slightly (and then some) unrealistic video showing them in action [youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6RbDkz737oA&w=420&h=315]

- The other, often overlooked aspect of dynamic stability is the long head of biceps

- This acts to hold the humeral head into the glenoid fossa; it’s pull is inf and medial therefore this is why it’s so important in dislocations as an active long head of biceps acts to keep the head out of the glenoid

For some truly great info on this check out Neil Cunningham’s shoulderdislocation.net and here’s a video of him in action reducing a dislocation. Note the massage of the biceps and supraspinatus.

and this one too, illustrating the anatomy

This is one of my favourite ways not to reduce a shoulder. Anybody else think he’s got a grade III AC joint injury and not a dislocation?

It’s worth mentioning scapular manipulation as it’s fairly easy and painless. And even I’ve managed to make it work!

I agree – it’s an ACJ dislocation – LOL

Love the way he had a quick drink of something seconds before they wrenched on his arm….

that and his friend saying he’s going to pull on three but actually pulling on 2!

that reduction is quite amazing!! Who would have thought a bit of a rub would relocate it?! I’m sure it’s more difficult than it looks!!

it’s impressive eh? I tried once on a posterior and it didn’t work. The guy is speaking tomorrow at this conference i’m at in dublin. All very exciting!

Pingback: Can Anyone Tell Me How I Got Here? « The EMBER Project