This is a transcript and list of resources for a lecture I gave at the European Society for EM conference in Berlin in October 2022. Hopefully I’ll get a recording of the lecture up here at some point.

I have done this talk for a few years but the big change is do with the problematic nature of the current definitions we have. It’s been a useful learning experience for me.

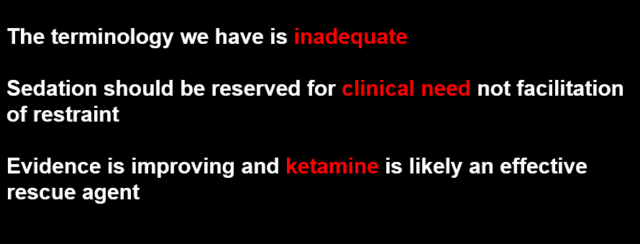

The first problem we’re going to run into is one of definition and terminology. We have all needed to provide chemical sedation for an agitated patient in the ED but what was their diagnosis? Did they have “acute behavioural disturbance”, did they have “excited delirium” did they have “hyperactive delirium with severe agitation”. All 3 of those terms have been used in fairly high level guidance documents surrounding the management of the agitated or uncontrollable patient. The problem is that it’s not clear at all if those terms describe a pathologic diagnosis in the same way we can define something like rhabomyolysis or myocardial infarction. The terms used to describe these syndromes are inconsistent and subjective and several organisations have now come out against their use in clinical practice.

So where has all the controversy stemmed from.

It came to my attention largely through the world-wide media attention following the murder of George Floyd and subsequent trial proceedings. At several points throughout the proceedings the defence used the term “excited delirium” a cause of Mr Floyd’s death rather than the means of restraint.

Interestingly, Martin Tobin, a fellow Irish doctor working in the states was brought in as expert witness for the case and made it very clear that he felt Mr Floyd had died of asphyxia not excited delirium or fentanyl toxicity.

Over the next year or two it has been made clear through several major policy statements and a lot of activity on social media that terms like “excited delirium” are problematic and have appeared on death certificates, often to the neglect of more likely causes like aggressive and dangerous practices of restraint. As you can imagine, especially in America, but no doubt prevalent world wide, people of colour or people and those from disadvantaged backgrounds have been disproportionately burdened by this. Hence there have been accusations that poorly defined clinical syndromes like this are contributing to racist law enforcement practices.

And while it would be nice to pin this at the feet of law enforcement, it was us as a medical profession who put these terms into documents and we need to be a lot more careful about we create these definitions.

There have been some recent improvements the APA making a very clear statement that >

“The term “excited delirium” (ExDs) is too non-specific to meaningfully describe and convey information about a person. “Excited delirium” should not be used until a clear set of diagnostic criteria are validated.“

American Psychiatric Association 2020

The UK forensic science regulator has been clear in saying

“‘Excited Delirium’ should never be used as a term that, by itself, can be identified as the cause of death. The use of Excited Delirium as a term in guidance to police officers should also be avoided.”

ACEP in the states have also walked back some of their use of the term excited delirium in recognition of its problematic nature.

All that is a very long winded and fairly formal warning at the beginning of this lecture: We need to be very careful in how we approach this tremendously vulnerable population, we need to be very clear that we are using sedation to manage their clinical needs rather than facilitating law enforcement. I was taught that excited delirium was a distinct clinical syndrome that may well kill the patient in front of me but a more careful look at how the term has been used suggests that methods to physically restrain may well be the bigger issue surrounding sudden death in this context. We also have to be aware that the same implicit biases surrounding race that seem to be an issue in law enforcement are likely equally to be at play in health care, something most of us would be very uncomfortable to admit.

For example in prior versions of the lecture I used slides like this to illustrate the type of patient we’re thinking of. While it’s somewhat amusing it reinforces the almost magical thinking that got us into this mess. The excited delirium definitions that we’ve been talking about used terms like “super human” strength or being “impervious to pain”.

These are patients who are maximally sympathetically stimulated not because of some nebulous magical gamma ray radiation but because they’re suffocating due to restraint or maybe there are sympathomimetic agents on board or maybe their mental health is in crisis.

So in lieu of an established definition or syndrome, we would be much wiser to stick to descriptive terms of the patient in front of you and focus on what their clinical needs and safety.

The frequency and type of patients you’re going to need chemical sedation for in the ED will vary widely depending on the population you serve. I have worked in smaller, regional EDs where this kind of presentation is extremely rare and when it does happen it is related to mental health with a smattering of alcohol misuse on the side. In the larger centres I’ve worked in you’re exposed to all the exotic chemicals that the big city has to offer and this may be a very frequent presentation. But you will find that rom city to city, and in particular from country to country, the poison of choice varies hugely.

For me to use something like ketamine for severe agitation is really quite rare, but the major substance misuse problems in central Dublin are alcohol and heroin and more recently GHB. Heroin in particular is not renowned for inducing agitation and violence. Indeed our current recreational substance of choice is typically GHB, a drug famous for producing profound unconsciousness rather than agitation. However if you work in a large north American centre you might be seeing severe agitation related to crystal meth on a daily or even and hourly basis.

So there’s a definite element of comparing apples and oranges with these patients I want to be clear that you should not walk out of this lecture and immediately blindly apply it to your own local population.

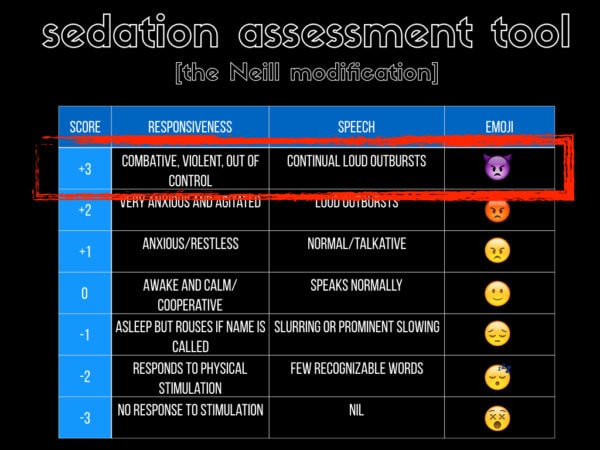

There’s clearly a spectrum of agitation and there are a number (almost 20 it seems) of different clinical grading systems for agitation and sedation. For example here’s an Australian one used in some of the chemical sedation literature. It runs from extremely agitated down to unconscious. It could easily be adapted to 21st century internet friendly version with addition of emojis

the real patients we’re worried about are the +3 patients.

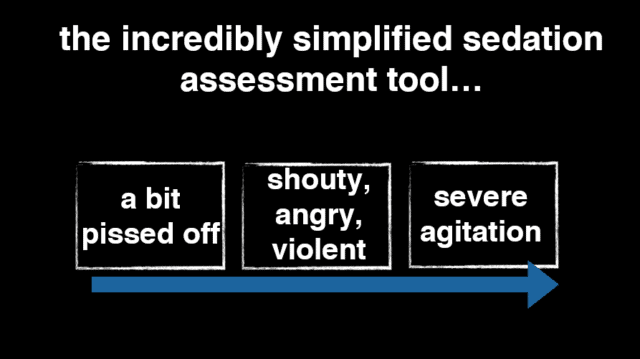

In my own personal practice I’m going to simplify it down even further.

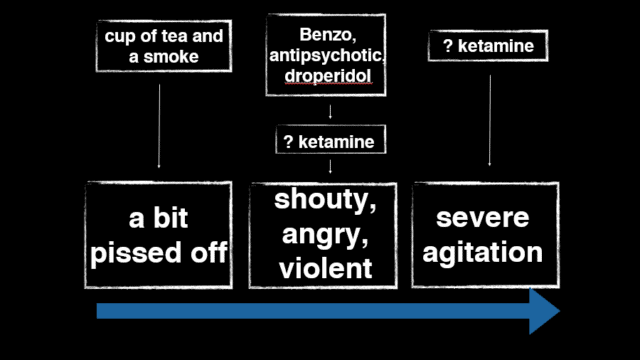

on the lower end of the scale (these would be the +1 and +2 of the sedation assessment tool), de-escalation is often all we need- do they just need some nicotine, caffeine and a bit of space. Some might be manageable with the old fashioned “cup of tea and a smoke” therapy

what do we do when this fails?

You have a lot of options. you can try a >benzo, take your pick. You can use >droperidol, an antidopaminergic, you can use an >anti psychotic like haloperidol or a newer generation version like olanzapine or you can choose >ketamine. Which one do you think has the best level of evidence behind it. >Currently the highest level of evidence for your starter medication is probably for droperidol. there is even some limited RCT vdata suggesting it’s best. there is a very interesting controversy/conspiracy that droperidol was killing people with prolonged QT but this is fairly well debunked at this stage and seems to be back in common usage. How many have droperidol? no one? the australians love it and still have it and the US loves it but can’t get it. So if we can’t use it what should we use first line?

but what about ketamine – where does it come in?

well first I’m going to give you a brief “how to” before we get to the limited evidence.

Ketamine is a dissociative anaesthetic – the commonest used agent in the world (driven by developing world). Imagine your thalamus as a major transport hub receiving signals from the body. The thalamus sorts all those signals out and sends them off to the cortex to make decisions about what to do about the stimuli. Effectively ketamine disconnects the thalamus from its sensory inputs and all of a sudden the brain doesn’t know that you’re amputating their leg or reducing their shoulder dislocation. It has a rapid onset both IV and IM. less respiratory depression and more preservation of airway reflexes than something like propofol. secretions commonly reported – remember atropine or glycopyrolate as a useful treatment.

if you’re going to give it you need the right people – this means either law enforcement or security staff. Reuben Strayer at his recent SMACC talk suggested the oxygen mask as a good tip 1) these guys are metabolically hyperactive and burning through O2 – giving them some extra might help us avoid some critical desaturation 2) it acts as a nice spit guard. i would make one comment -never put your hand near a mouth if you want to keep all your fingers. so points for the oxy mask and points off for fingers near the mouth

the environment – usually these patients are being restrained somewhere like an ambulance bay or a poorly lit and resourced psych assessment room. it’s fine to give the ketamine there but as soon as it starts to take effect you need to move to high dependency area. Basically you’re doing procedural sedation here and you have to provide the same level of care.

now is the time you can start your work up – is there sodium channel blockade from cocaine on that ECG – is there a severe metabolic acidosis, now is the time to get your head CT if you need it. get your vital signs now (you won’t have had a chance before) These patients often have serous pathology and in many ways our work is only starting once we have control of the situation

IM is the route of choice , the dose is 4-6mg/kg but i find>5 easier to remember. — if you have an IV line and easy access then great but the risk and difficulty getting an IV while 5 security staff sit on your patient is not really justified when you can give an IM dose through their clothing much quicker and with less risk

the really important thing is to check what > dose you have in the cupboard. the last time i did this we one had the 50mg/ml concentration and i needed to give two separate 4ml IM injections. If you can, get the 100/ml concentration…

In studies and descriptions of acutely agitated patients there is frequent reference to autonomic dysfunction and indeed many of these patients will be hypertensive and tachycardic and even febrile when they present. The question is usually raised that ketamine has some sympathomimetic effects and surely this could make their autonomic state worse but the evidence (as limited as we have) shows just the opposite. That’s not really surprising if we stop to think about it. The patients we are looking after currently are maximally sympathetically stimulated. If you could get vital signs their heart rate would be 180, their BP would be 200 systolic. their adrenals are squeezing out adrenaline for all they’re worth. It’s not surprising that providing an anaesthetic and removing the noxious stimuli of the 5 security staff will knock that HR down to 110 and the BP down to 150

so where might ketamine come in our management of these patients? At the lower end we’ve decided on the cup of tea and a smoke treatment. At the shouty/angry stage we’re likely to need something like a B52 (or droperidol if you have it). Ketamine might have a role if this fails. But once we get to the extreme agitation stage some folks are even suggesting ketamine as first line. The general preponderance is that ketamine should be a rescue treatment but some groups, like in hennepin in minneapolis in the states, they have been using ketamine as first line in the most severe cases for a few years now.

But what about the evidence. From a strict EBM perspective it’s historically been pretty poor. A collection of anecdotes does not equal data etc… Remember thought that the evidence for what we currently do, the B52 or the benzo/antipsychotic combo isn’t that great either… For ketamine it’s all low level evidence, cohorts, case series, before and after type comparisons… > This table is from a steve green editorial on one of the recent studies that collects a lot of the case series. The message overall is – it works, but you end up intubating a significant number. The evidence has improved significantly in the past few years

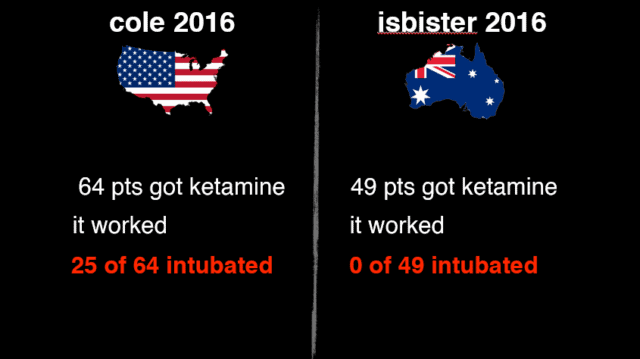

the big issue, the big concern is the intubation rate – I’m gonna compare two different recent papers to illustrate this. This is definitely comparing apples and oranges. Cole was a prehospital pseudo randomised trial with ketamine as first line. The Geoff Isbister paper was a subset of the DORM 2 trial of ED patients who failed droperidol. But what i want to compare is good old fashioned national rivalry. In cole 64 got ketamine, in isbister, 49 got ketamine. Overall it worked. but in the cole paper 40% were intubated, in oz with the same dose none were intubated. I suspect (and i have zero evidence for this…) that this may be just a practice management difference. From chatting to folk in north america it seems the threshold for intubation is much lower than practice in the UK and Oz is. We have a lot less ICU beds for starters and we often defer intubation on people with low GCS (particularly from intoxication because we know the pathology involved and we know it will get better.

It’s not that intubating these guys is a failure – they get a secure airway and ICU care – that’s great – the problem is the push back i would get in a system like mine where we rarely intubate these type of patients – if that suddenly changed that would be a big resource issue. If you’re comfortable with the dissociated patient (often GCS in the low single figures – described as GCS3K) then they probably don’t need tubed…

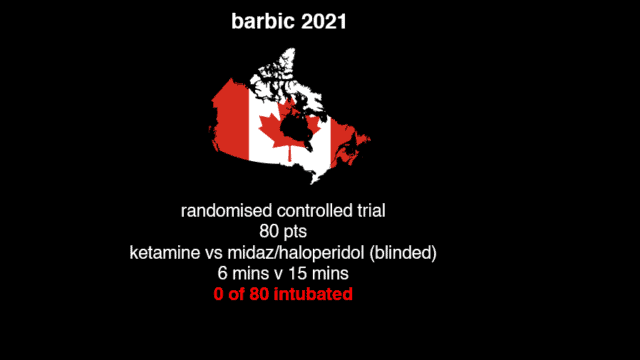

But we have new data from the last time I gave this talk that hopefully makes things clearer. The most recent RCT is the Barbic paper out of western Canada. It’s a great addition to the literature and the most substantial RCT out there. They enrolled pats with a +3 on the RASS which is way up there with our angry face emoji. They were randomised to either a decent dose of ketamine at 5mg/kg IM or a 5mg midaz/5mg haloperidol combo, akin to the B52 we were talking about earlier. This was a blinded trial which is great methodology for something like this.

The main take home is that they achieved appropriate sedation much quicker in the ketamine group than the midaz/haloperidol group. No one was intubated. There were a couple of brief laryngospasm events reported in a single patient in the ketamine group both managed with simple airway maneuverers.

The high intubation rate in some of the prior papers attracted a lot of attention and there have been a lot of chart reviews published by EMS agencies in the last few years highlighting that the intubation rate is likely much lower than that seen in the cole RCT.

But we have new data from the last time I gave this talk that hopefully makes things clearer. The most recent RCT is the Barbic paper out of western Canada. It’s a great addition to the literature and the most substantial RCT out there. They enrolled pats with a +3 on the RASS which is way up there with our angry face emoji. They were randomised to either a decent dose of ketamine at 5mg/kg IM or a 5mg midaz/5mg haloperidol combo, akin to the B52 we were talking about earlier. This was a blinded trial which is great methodology for something like this.

The main take home is that they achieved appropriate sedation much quicker in the ketamine group than the midaz/haloperidol group. No one was intubated. There were a couple of brief laryngospasm events reported in a single patient in the ketamine group both managed with simple airway maneuverers.

The high intubation rate in some of the prior papers attracted a lot of attention and there have been a lot of chart reviews published by EMS agencies in the last few years highlighting that the intubation rate is likely much lower than that seen in the cole RCT.

Take home points:

Great work Andy. Thanks – really comprehensive.

Thanks for this transcript of your great talk in Berlin. I’ve been there listening to you and it was really great…I have two questions to you:

1- What do you think about antiphycotic drugs after ketamine to prolong sedative effects after the dangerous loop of agitation has been interrupted

2- What do you think about using ketamine in patients you suspect the agitation derives from drug abuse. I mean, lot of people think it could ne a contraindication because you cannot predict the overlapping effects.

Thanks a lot

1) all depends on the situation and whether you think ongoing sedation will be needed

2) the (very few) times i’ve done this have involved substance abuse. The ketamine is not treating anything it’s simply allowing you control to get a diagnostic work up done and allow the intoxications time to wear off.

Thanks!